The post Polaris Letter of Support for the ENABLERS Act first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Polaris Letter of Support for the ENABLERS Act first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Systemic Change Matrix: Disrupting and Preventing Human Trafficking first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Systemic Change Matrix: Disrupting and Preventing Human Trafficking first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Is Your Local News Protecting Illicit Massage Business Trafficking Victims? first appeared on Polaris.

]]>

What you might not have realized is that many of the women in the photos are actually human trafficking victims. Instead of being protected like other victims of crime, they are being exposed and publicly shamed.

Why are victims not being identified as victims?

Human trafficking victims rarely self-identify as victims to police. That is why police raids are not effective ways of helping victims or reducing trafficking in massage businesses. In massage industry trafficking, self-identification is probably less likely as the victims are most often recent immigrants who likely have a limited grasp of the language and – if they are from some countries – a well-honed and well-justified distrust of police.

What’s the fix?

We are asking for a couple of things – one pretty simple, one less so.

First and foremost, just stop identifying people arrested in these raids. In fact, stop reporting on these raids at all – at least not in a perfunctory, one-day blotter story kind of way that defies context. That’s the easy part. At the very least, treat the people arrested in the massage industry vice operations as you would treat any other victim of sexual abuse. These are high-volume, low-pay, inherently abusive operations in virtually every instance, whether the abuse amounts to trafficking or not.

Next, do better, deeper reporting. We recognize that this is challenging in today’s newsrooms, where you barely have the bandwidth to eke out a few paragraphs from the police scanner. But we ask that you hold on to the idea that there are stories to be told here beyond cops-and-bad guys.

Consider, for example, the economics of these businesses – the sheer volume of trade that would have to occur to make them profitable, versus the number of potential buyers of sexual services in your town. Who are the buyers? And why do we never hear about them?

You might also consider actually tracking what happens in this case, after the arrest. Are the women provided with translators who actually understand them? What about men? Is this an entirely women-owned and operated business or is there someone else who is profiting from it who was not arrested? How about buyers? Did they have to pay a fee or fine or were there any other consequences? Where the consequences worse for the women than the buyers?

Please contact us at media@polarisproject.org if you would like to talk through this further.

What can you do?

The next time you see a massage business story that exposes potential victims, or simply doesn’t dig deep enough, use your voice to reach out to the reporter or publication. Here are two ways you can have an impact:

1. Send the reporter an email

A quick email is an easy, private way to make your voice heard. Here’s a sample email you could write:

Subject: Massage parlor trafficking

Hi [reporter’s name],

I just read your piece, “Local massage parlor raided” and wanted to suggest that you reconsider your decision to publish the names of the women arrested. These women may well be victims of sex trafficking. If they identify as victims of trafficking or not, they are certainly working and living in an abusive situation. Shaming them publicly is of no value to the community you serve.

Thank you,

[Your name]

When drafting your email, keep in mind that the reporter likely has no idea that massage parlors are a common venue for human trafficking. Aim to be kind and helpful in your outreach.

You can usually find a reporter’s contact information by clicking on their byline, or by looking them up on Twitter (tip: many reporters have their email addresses in their Twitter bios). If you can CC their editor as well, even better! (that might take a little more digging – editors are usually listed on the publication’s “Staff” or “Contact Us” page).

2. Submit a letter to the editor

This option requires a little more effort than an email, but it’s extremely powerful because of how many people in your community may read your letter.

A letter to the editor is a short (usually 250-300 words maximum) letter published in the Opinion section of the newspaper, expressing a reader’s concerns. When you identify an article you’d like to comment on, the first thing you should do is search for the “Letter to the Editor” submission guidelines for the publication. They’re usually on the Opinion page and will include the word limit and where to send your letter (here’s what the Chicago Tribune’s guidelines look like).

Once you know the parameters, you can make your case about why the article you read doesn’t go far enough in making the connection to potential human trafficking, and how the publication can protect victims going forward by not sharing identifying information.

Some potential points to emphasize include:

- It’s possible human trafficking might be involved in this story

- Reasons potential victims don’t typically self-identify to police

- Ways to dig deeper into the story (use the suggestions listed earlier in this post)

Here’s an example of a letter we had published recently in the Chicago Tribune that hits all of these points. A powerful letter that is likely to be published will be uniquely responsive to a specific article.

Your voice can make a big difference!

There’s no law prohibiting media outlets from publishing the identities of sexual assault victims. The reason none of them do it is because they know it’s not ethical — and that they would face tremendous public outrage if they did.

It’s time to help the media understand that potential trafficking victims belong in this same protected category, and that there’s a deeper story to tell. Your email or letter to the editor can truly be a catalyst for change in your community.

The post Is Your Local News Protecting Illicit Massage Business Trafficking Victims? first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Netflix’s Ozark, Money Laundering, and Massage Parlor Trafficking first appeared on Polaris.

]]>Money Laundering 101

In case you are imagining a complicated washing machine only mobsters have, Jason Bateman — through his Ozark persona Marty Byrde — provides a helpful “Money Laundering 101”:

“Say you come across a suitcase with $5 million bucks in it. What would you buy? A yacht? A mansion? A sports car? Sorry, the IRS won’t let you buy anything of value with it. So you better get that money into the banking system. But here’s the problem — that dirty money is too clean. You have to make it look like it’s been around the block. You need a cash business, something pleasant and joyful, with books that are easily manipulated. You mix the $5 million with the cash from the joyful business. That mixture goes from an American bank to a bank from any country that doesn‘t have to listen to the IRS. It then goes into a standard checking account… your work is done, your money is clean.”

In Ozark, we see Bateman’s character Marty start a major money laundering operation after he comes under the threats of a cartel boss (to be fair, Marty was stealing from him). In order to save his life, Marty guarantees he can launder over $500 million in drug money in the Ozarks, a mountainous vacation spot replete with cash-rich businesses. So he packs up his well-to-do Chicago family and heads to Missouri in search of unsuspecting cash-heavy businesses he can manipulate to make good on his word.

How money laundering works in massage parlors

Human traffickers selling sex in massage parlors have the same problem on their hands as the cartel boss. Even though they’re already operating behind the storefront of a business, they still have the problem of explaining where all the extra cash is coming from. For example, “Relax Spa” may be advertising $40 an hour for massage, but accepting a $100 “tip” under the table for commercial sex. That adds up to a lot of extra money.

Massage parlor in strip mall, Tampa, FL

According to Polaris research, the massage parlor trafficking business is a $2.5 billion industry annually. How do traffickers avoid suspicion with this much money coming in? For starters, illicit massage businesses (IMBs) can hide some extra cash by altering their books internally, i.e. reporting items as costing more than they actually did and thereby laundering the money themselves.

Traffickers also wire money abroad, entirely skirting the need to clean the money for use in the United States. Some also funnel the extra money through other businesses they have in their network, such as another massage parlor, nail salon, or restaurant.

Sample massage parlor trafficking network

It all adds up

In Ozark, Marty Byrde started out with a crumbling lakeside motel, and quickly moved into the strip club and construction businesses to pick up the laundering pace. At the motel, Marty used renovations as a laundering tactic. For example, he purchased 16,000 sq. ft. of carpeting at $0.69/sq. ft., but tracked it on the motel’s accounting ledger as 32,000 sq. ft. of carpeting at $8.75/sq. ft.

That equates to $270,000 in illegal money that now looks perfectly legitimate. He then ordered four air conditioners for the motel’s rooms, but expensed 25. He made another $150,000 appear legitimate by inflating the costs of redoing the employee locker rooms.

As Marty says, money launderers are “not criminal geniuses, just pathological liars on the path of least resistance.”

This can be done anywhere. As Marty says, money launderers are “not criminal geniuses, just pathological liars on the path of least resistance.” Marty’s next move is to take over a strip club, a business where customers routinely pay in cash, and inflate the proceeds.

Hiding business ownership

The strip club is owned by a shell company (a corporation that exists in name only) to hide its true ownership. Marty’s name is conveniently nowhere on the business records. If you did some digging, you would find the club is officially owned by a company based out of Panama, linked to no individual person’s name at all.

Hiding business ownership like this is not only legal, it’s common. For Marty, such a setup provides protection by shielding him as the responsible party. Many IMB owners use shell companies for the same reason — to hide who owns their massage parlors, as well as other businesses in their networks. This makes it as difficult as possible for investigators to trace the flow of illegally-gained money and figure out who is to blame.

Marty planning his next move (source)

As described in a recent Polaris report, the United States is one of the easiest countries in the world for owners and operators of businesses to hide business ownership. Neither the federal government nor the states require companies to include the name of the “beneficial owner” (the person who actually controls the business and receives its profits) in standard registration paperwork.

Although requirements may vary slightly by jurisdiction, the owner’s name can often be left entirely blank; filled in with the name of a registered agent or other paid point of contact; or registered under the complete anonymity of an empty shell company.

Following the money

Fortunately for law enforcement, money launderers leave clues behind. By investigating money laundering, law enforcement can build cases to shut down entire networks of IMBs and their operating fronts.

Shutting down the entire trafficking network by focusing on business operations is far more effective and victim-centered than some of the typical interventions we see now — particularly raids where individual workers (potential trafficking victims) are arrested for prostitution.

Storefront massage parlor, Los Angeles, CA

Worker-focused raids do not work because the owners and operators of IMB trafficking rings, hidden behind their business anonymity, can easily recruit new victims or simply rotate them to and from other parlors in the trafficking network. The victims, meanwhile, get no relief or protection and are now at odds with the law and even more convinced of their trafficker’s prowess.

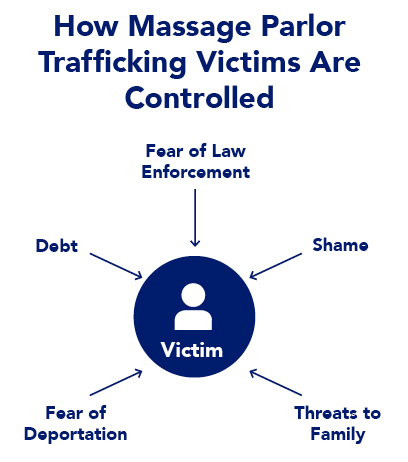

Traffickers go to great lengths to make sure that their victims fear law enforcement and are therefore unlikely to testify against them. Focusing on money laundering thwarts these manipulative efforts by removing the burden of conviction from the shoulders of victims.

Building a money laundering case is a powerful way to take down traffickers, but it requires significant time and resources. All the while Marty and his family were buying up businesses to launder money, at the risk of life and limb to those around them, the FBI was watching, waiting, and hoping to build a case. It will be interesting to see where their investigation leads in the upcoming season.

The post Netflix’s Ozark, Money Laundering, and Massage Parlor Trafficking first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Human Trafficking in Massage Businesses: A Deeply Manipulated Sense of “Choice” first appeared on Polaris.

]]>Massage business trafficking is happening in plain sight, in businesses that operate as if they are legal massage or bodywork establishments. It persists because we choose to ignore it — as something harmless, as something inevitable, or both: at best, a victimless crime. At worst, a public nuisance.

The real story is much harder to ignore. The women trafficked in massage businesses are typically immigrants from China or South Korea, usually mothers between the ages of 35-55 who are looking for a way to support their families. They are often lied to or seriously misled about the type of work they’ll be doing, by traffickers who know they have debts they need to pay or are otherwise in no position to say “no” to a source of income.

Once they are at the massage business, traffickers step up their control with a combination of manipulation and blackmail. A woman who speaks little English, whose identification documents are held by traffickers, whose finances are controlled by traffickers, and who has been transported by traffickers to an unfamiliar place, is told that she has the “choice” to provide commercial sex or to leave and take care of herself.

Traffickers have told her that if she leaves no one will help her, that the police are corrupt and won’t listen to her or believe her, that she will be arrested for prostitution or deported, and that her family will be told the shameful story that she is working in the sex industry in the United States, and will be required to pay off her debts. Given this situation, there is no real choice for the victim. Either she stays at the massage business, abiding by the rules set by the trafficker, or risks losing everything.

Due to this deeply manipulated sense of “choice” and pervasive feelings of shame, victims of massage business trafficking are very unlikely to immediately self-identify as trafficking victims to police or even to service providers. It takes specially-trained service providers and law enforcement officers to understand this dynamic and support victims, while carrying out thorough investigations that will ultimately hold the traffickers accountable.

Min’s Story*

Min came to Southern California from the Fujian province in China. She had dropped out of school in the 9th grade but had worked hard all her life. Her husband had always gambled and now had more debts than they could pay, so she came to visit a friend in the United States and look for work. She found an online ad for women to work as massage therapists near Los Angeles and was promised $6,000 a month with free housing.

She took a bus to the location on the ad and was met by a driver. Min showed the driver the name of the business and the address she had been given. The driver then drove for some time to an apartment where two other women were staying. In the morning, a second driver came to pick everyone up to take them to the massage business. On her first day, Min was told that in order to earn the money she had promised her family, she would have to engage in commercial sex.

Min had no idea where she was or how to contact the first driver to get back to the bus station. Min stayed and when she was able, told her family everything was fine. Min was deeply ashamed this had happened and never wanted them to find out. Whenever she came close to asking a customer for help, her manager would threaten to call the police, who she said would deport her and tell her family how shameful she had been. Every few weeks, Min would be moved to a new apartment and new business. All she knew was that she was still somewhere near LA.

Eventually, she wound up in a business that police were targeting. When they came to shut it down, they arrested the traffickers, not Min. The police then told Min she was actually in Illinois, nowhere near LA. The police helped connect Min with service providers in Illinois and then California. The service providers helped Min understand her rights and helped her enroll in English classes. Min is in the process of receiving a visa specifically for victims of trafficking, the T visa. Now she is honestly able to tell her family that everything is fine.

*This story is a composite based on dozens of reports by survivors, service providers, and law enforcement officials.

The post Human Trafficking in Massage Businesses: A Deeply Manipulated Sense of “Choice” first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Is There Massage Parlor Trafficking in my Community? first appeared on Polaris.

]]>Concerned community members can play an important role in ending massage parlor trafficking, but it’s critical that it’s done in a careful way.

Simply calling police and urging them to “shut down” a business that looks sketchy may not actually have the intended effect. That’s because most of these businesses are part of organized crime networks and if one location is closed, traffickers will simply shift the women to another. Worse yet, such police operations can often result in trafficking victims being arrested and booked on prostitution charges.

You should also avoid entering massage parlors you think may be IMBs, attempting to talk with potential victims, or taking actions designed to draw attention to a particular business (like protesting outside) — all of which can be damaging to victims. Attempting to talk with potential victims can alert traffickers (who are often monitoring the women by camera) and drawing attention to the business can lead the traffickers to pick up and move their entire operation before victims can be identified and provided with services. If you suspect that a location is an IMB, you should instead call in a tip to the National Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888).

To have even more impact, you can help make it more difficult and less profitable for traffickers to operate in your community by asking your local legislators to pass stronger business regulations. One example of a way a local ordinance for massage businesses could be made stronger is by including a provision requiring that customers enter the business through an unlocked front door, as opposed to a more hidden, security-controlled entrance around the corner or in the back. Sex buyers prefer the privacy of a discreet entrance, so this kind of regulation is likely to hurt a trafficker’s business.

Since all communities are different, there is no one-size-fits-all set of regulations to help end trafficking. It’s really important that all stakeholders — particularly massage therapists — are involved in the conversation. To get the ball rolling, you can email your city or county council members to let them know that you want strong, victim-centered business regulations in your community. And then follow up by showing up at your next city or county council meeting, and speaking during the public comment period to let your representatives know that you take this issue very seriously.

The post Is There Massage Parlor Trafficking in my Community? first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Corporate Secrecy Fuels Human Trafficking in United States first appeared on Polaris.

]]>Click here to read the report.

Polaris examined open-source data on over 9,000 illicit massage parlors and their networks in the United States in a report on illicit massage parlor trafficking released in January. Through that analysis, Polaris found only about 6,000 illicit massage parlors had business records. Of those 6,000 parlors, only 28 percent had an actual person listed on the business records. Furthermore, only 21 percent of the 6,000 business records specified the name of the owner—and even in those cases, there is no way to know if the information provided is legitimate.

“Law enforcement can’t effectively combat human trafficking if they don’t have all the information they need, and the current laws are helping traffickers cover their tracks,” said Rochelle Keyhan, Polaris’s Director of Disruption Strategies. “Policymakers must pass corporate transparency legislation that gives law enforcement the tools they require to shut down massage parlor trafficking.”

“The U.S. is now the easiest place in the world for criminals to set up anonymous companies to hide their identities and launder money,” said Gary Kalman, the Executive Director of the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition. “Polaris’s report provides clear and convincing evidence that this anonymity is being used to shield traffickers. It’s time we removed the veil of corporate secrecy and hold these criminals to account for their crimes.”

Polaris urges changes to federal laws to require businesses to disclose owners and to make that information available to law enforcement. Congress is currently considering a number of bipartisan pieces of legislation that meet these standards.

Additional takeaways from the report include:

- What is required on business registration paperwork can be different for each local jurisdiction. Depending on the requirements, owners’ names could be left blank, the name could be filled with a registered agent or someone else paid to be the front person or point of contact, or an anonymous shell company could be used. All of this obfuscation is perfectly legal.

- Typical law enforcement activity around illicit massage parlors has, historically, involved raids in which officers sweep into the facility and arrest everyone on the premises, including victims. These raids are highly unlikely to net the actual owners of the businesses, as they are rarely on site or even necessarily involved in the day-to-day operations of the massage venues. The frequent arrests of victims—not owners—is not effective in ending trafficking; in fact, it only strengthens the traffickers hold on victims as the threat of arrest is often used to keep victims trapped in their situations.

- To effectively and sustainably target massage parlor trafficking, law enforcement must undertake organized crime investigations, which focus on ownership by looking into money laundering or tax evasion. This would shut down entire networks, meaning that the victims could not simply be moved around until the police interest had calmed down. Unfortunately, the ability of businesses to obscure ownership and therefore network ties, makes it incredibly time-consuming, and sometimes impossible, for law enforcement to undertake such investigations.

For more information on beneficial ownership and incorporation transparency, click here to access the Fact Coalition’s resources.

People can be connected to help or report a tip of suspected human trafficking by calling the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888, texting “BeFree” (233733), or chatting at www.humantraffickinghotline.org.

###

About Polaris

Polaris is a leader in the global fight to eradicate modern slavery. Named after the North Star that guided slaves to freedom in the U.S., Polaris acts as a catalyst to systemically disrupt the human trafficking networks that rob human beings of their lives and their freedom. By working with government leaders, the world’s leading technology corporations, and local partners, Polaris equips communities to identify, report, and prevent human trafficking. Our comprehensive model puts victims at the center of what we do – helping survivors restore their freedom, preventing more victims, and leveraging data and technology to pursue traffickers wherever they operate. Learn more at www.polarisproject.org.

The post Corporate Secrecy Fuels Human Trafficking in United States first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Hidden in Plain Sight: How Corporate Secrecy Facilitates Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Parlors first appeared on Polaris.

]]>What is unique about this form of trafficking is that massage parlor traffickers actually go through the process of registering their businesses as if they were legitimate. Conceivably then, it should be relatively simple to determine the basics about these businesses — such as what products or services they provide and who ultimately controls and makes money from the business. The actual or “beneficial” owner would then in most cases be the trafficker and could be prosecuted as such.

In reality, the laws governing business registration are almost tailor-made for massage parlor traffickers to hide behind.

The post Hidden in Plain Sight: How Corporate Secrecy Facilitates Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Parlors first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post The Typology of Modern Slavery: Defining Sex and Labor Trafficking in the United States first appeared on Polaris.

]]>For years, we have been staring at an incomplete chess game, moving pieces without seeing hidden squares or fully understanding the power relationships between players. The Typology of Modern Slavery, our blurry understanding of the scope of the crime is now coming into sharper focus.

Polaris analyzed more than 32,000 cases of human trafficking documented between December 2007 and December 2016 through its operation of the National Human Trafficking Hotline and BeFree Textline—the largest data set on human trafficking in the United States ever compiled and publicly analyzed. Polaris’s research team analyzed the data and developed a classification system that identifies 25 types of human trafficking in the United States. Each has its own business model, trafficker profiles, recruitment strategies, victim profiles, and methods of control that facilitate human trafficking.

The post The Typology of Modern Slavery: Defining Sex and Labor Trafficking in the United States first appeared on Polaris.

]]>The post Debt vs. Debt-Bondage: What’s the Difference? first appeared on Polaris.

]]>Now consider what debt might mean for victims of human trafficking. For them, debt is often an insidious means of control used to keep them trapped. Traffickers convince victims that they have no other choice but to work for the trafficker and pay back exorbitant amounts of debt. Oftentimes, victims will also get hit with unreasonable interest rates, sometimes as high as 400%. Controlling another person through debt may sound less extreme than physical force, confinement, or violence, but debt bondage is a financial shackle that is just as debilitating, fraudulent, and coercive.

Connecting the Dots to the Illicit Massage Business Model

Debt bondage is a key method traffickers use to force women in illicit massage businesses to perform commercial sex. Traffickers promise legitimate jobs in the United States to women from other countries, like cooking, waitressing, or even a job as a massage therapist, but then charge the women $10,000 – $40,000 to enter on valid visas (from RestoreNYC Client Findings). Like other trafficking victims, these women have been promised a high-earning job that will quickly pay off their debt in a short period of time. But once the women borrow the money for a visa to the United States, they are under the traffickers’ control and their American dream is shattered.

Why would a woman take on an incredible amount of debt to engage in commercial sex in the United States?

In short: they’re lied to by their traffickers. The target group for exploitation in Illicit Massage Businesses are women who have minimal education, previous trauma from abusive relationships, or other types of financial drivers, such as young children (from RestoreNYC Client Findings). Advertisements targeting this group of women often misinform them of the work they’re going to be doing, as well as the amount of money they will earn in a given week or month.

Women respond to the advertisements because of the promise of a well-paying job and with the hopes of better opportunities. However, once here, they incur a debt that would make most of us cringe and are left with no choice but to pay it off by engaging in commercial sex. The sad reality is that the women don’t have a choice. They are pushed to do whatever it takes to “please the customer,” which often involves “happy endings” or “specials with massage[s].”

The Never Ending Cycle of Debt

The nightmare doesn’t end when the women “pay off” their initial debt from getting to the United States. Traffickers know how effective debt bondage is as a control mechanism, so they create opportunities that encourage the women to incur more debt. Women may accrue more debt through fees for basic living needs — sometimes being charged $200 per week for food alone. Even purchases for toiletries like soap and toilet paper are added to their debt at excessively high charges.

Debt can be psychologically and emotionally crushing, especially when you have limited means to pay the debt. Debt bondage an ideal tactic for traffickers in illicit massage businesses to keep victims in an unending and all-consuming situation because it keeps victims silent, psychologically broken, and enslaved.

Photo credit: Flickr / Tax Credits

The post Debt vs. Debt-Bondage: What’s the Difference? first appeared on Polaris.

]]>